What is the modern view-source?

I started working on the web in 1994 and I've been privy to the evolution and complication of the web and its component technologies.

The web was much simpler then, with a limited set of tags and little CSS and JavaScript that only changed the look of items on the page. If we wanted applications we had the option of Perl or C to create CGI script and roundtrips to the server for each request.

We've improved considerably from those days to where the web is now. We have hundreds, if not thousands, of projects that we can learn from but that's not the answer.

Frank Chimero's Everything Easy is Hard Again presents the view of someone who left the web design business and returned a few years later to find out how much more complex the web had become and how much more we do for the sake of doing it.

It's from this viewpoint that messages like this worry me.

“Can we agree that, in 2018, human-readable “View Source” is a constraint the web can discard? I benefitted from “View Source” too, but today we have an embarrassment of resources and open source examples I would have killed for as a kid.”— Tom Dale

Jonathan Snook and Christian Heilmann present interesting positions on the issue of having text-based renditions of our content in addition to what's interpreted by the browser to provide the output on-screen.

Snook writes towards the end of his post:

The sites some build may be simple static sites, befitting of a simple View Source. The sites some build may be compiled and bundled and requiring tools that allow us to dig deeper. Just because you don’t need those tools doesn’t mean that somebody doesn’t need those tools.

Chris Heilmann makes three points that I think are interesting to look at:

Except for a few purist web sites out there, what you see in your current device isn’t the code of the web site.

The bytes sent to the browser may be different because the browser decided what image to load or the JS engine decided what script to load when using modules and providing a fallback for older browsers. Even if the loading process injected JavaScript, styles, or images into the page the source of the document will still match what's rendered.

Code sent to the web is often minimized and bundled. Developer tools give you options to pretty-print those and thus make them much more understandable.

DevTools in all modern browsers work hard in letting you see what the code you're viewing really look like and give you a human-readable version of the code, within the limitations of the tool used to create the minimized scripts and bundles:

- Minimized JavaScript expanded by Chrome DevTools is still nearly impossible to read when the tool that produced the minified code also mangled variable names to single characters

- Looking at the code generated by Webpack you get more lines of Webpack code than bundled code, it's difficult to figure out which bundle contains the script.

Of course, it is great that there is no barrier to entry if you want to know how something works. But the forgiving nature of HTML and CSS can also lead to problems.

I agree that HTML can cause problems but it's on us as developers, as standards organizations and as people who teach about the web that it got to where it is. Some developers embraced the tag soup markup (a defensive measure to make sure that the web still worked in modern browsers) and produced markup that would never validate as HTML in any strict validator... and we claimed it was OK and we moved on. As a result, web browsers must be forgiving because developers took the shortest path to a result rather than taking the correct path to the solution.

We need to put the best examples front and center so that people who copy and paste code will find semantic correct HTML rather than tag soup garbage.

But there are more fundamental questions than whether we should have view source for our web content or whether view source is a constraint to current web development.

The entry barrier #

What do we need to learn in order to do basic web development? What APIs and what technologies? It's not enough to know HTML, CSS, and JavaScript but you have to make selections about build systems (either your own choice or whatever your project is using), what version of JavaScript will you use, whether you want to use templates for your project and, if so, whether to use native templates or a templating engine. The choices keep increasing and get more complicated with new technologies and frameworks being released frequently.

Pointing people to Github as a resource means that they know what they are looking for and that they are proficient at the target language, Javascript in this case, to recognize the code and what it does. This wasn't always the case for me and still isn't when a beginner looks at the code. When I looked at a page it took me a while to figure out what the code did and, several times, I had to copy the code into a page of my own and then play with it until I figured it out or did what I wanted it to do.

But now with all the minimization and bundling of our code it has become very hard, if not outright impossible, to do that kinds of "learn by doing" because there is no easy way to identify mangled variables or figure out how many Webpackk generated bundles we need to keep to make sure that the code works.

Another of Tom's quotes in the same Twitter thread makes me wonder if I'm missing something. The tweet in question:

I'll go a step further: insistence on human-readable formats on the web is a pretty intense display of Western privilege. Binary formats are important for reaching people with slower devices and capped data plans. I'll happily sacrifice my own nostalgia to achieve that goal.

I don't think that a binary format will change the way we address transfer and weight of our web content, if nothing else, we'll be throwing the same volume of material in a binary format, thus removing any advantage that the binary format offers.

It's not just the network time that'll kill your app's startup performance, but the time spent parsing and evaluating your script, during which time the browser becomes completely unresponsive.

On mobile, there are additional startups that need to happen (cell modem startup and connection, the communication between the cell tower and the Internet, potentially powering up the high-end CPUs to do the heavy lifting on parsing your JavaScript) those milliseconds rack up very quickly.

See this presentation from Alex Rusell to get a better understanding of the challenges of the mobile web. It's from 2016 but the underlying principles have not changed.

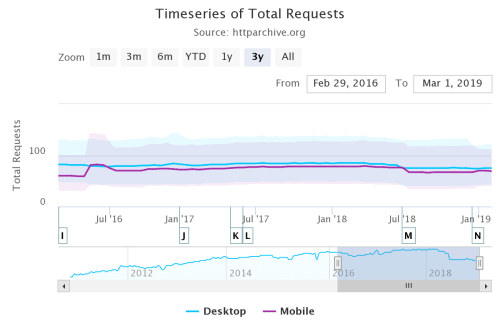

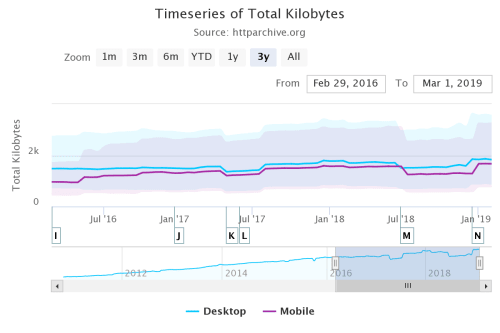

The following figures show how much stuff measured by the median number of requests and size in kilobytes have grown in a 3-year period from 2016 to March 2019 (data taken from the HTTP Archive's state of the web report).

Timeseries of median total requests over a 3 year period

Timeseries of total kilobytes over a 3 year period

I think that to solve the performance problem we've created, we have to become more restrictive of what we can and cannot do on the web. We can start with enforcing best practices for any one of the many performance patterns available... RAIL and PRPL offer actionable goals for you to pursue but actually meeting the performance goals is up to you.

This is also about being serious in creating a performance culture in our organizations. Addy Osmani and Lara Hogan provide good introductions to performance budgeting.

Tools like Performance Budget Calculator, Performance Budget Builder and Browser Calories can help in building the budget once we figure out what a budget is and decide that we want to use one for our project.

Smashing magazine publishes an annual front-end performance checklist. The 2019 edition provides sensible and actionable steps for you to follow if you want to improve performance on your site or app.

Once we have the budget we need to enforce it. Webpack has a plugin that will warn (or error out) if you go over a pre-defined bundle size and Pinterest has created an ESLint rule that disallows importing from certain packages.

How we address these performance requirements and how seriously we enforce them is up to us. But I see no other way to really to get out of this bloated mess we've turned our web applications into.