Improving Font Performance: Introduction and the bulletproof syntax

Talking about web font performance is more than just talking about adding the fonts to a page using @font-face. That's just the beginning of our quest for performant fonts.

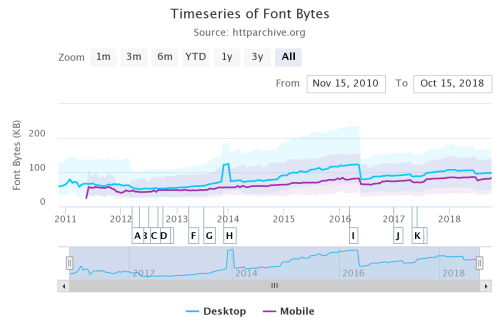

Because of their size fonts tend to be some of the largest components of any web pages. According to the HTTP Archive, the median of requested fonts is 98KB for Desktop and 83.4KB for mobile.

Making our fonts performant is particularly important when working with large variable fonts; Roboto VF is 976KB when compressed with WOFF2 and, if not cached, can significantly impact the performance of the page.

Background: @font-face and downloadable fonts #

We tend to think of downloadable fonts as a new phenomenon but it isn't. In 1998 browsers started shipping support for the @font-face CSS declaration… now developers could use digital fonts in their pages, right?

Not quite. While browsers supported the syntax they supported different font formats: Netscape supported TrueDoc from Bitstream and Microsoft supported Embedded Open Type (EOT), which also provided a layer of encryption for their downloadable fonts.

The other problem was that you didn't have to own fonts in order to use them as downloadable assets. There was no way for foundries (the companies that created fonts) or developers to restrict access to the downloadable fonts.

Many foundries were concerned about piracy even in the encrypted EOT format so, for a long time, they withheld licenses for downloadable fonts.

Without good fonts, the whole idea of downloadable fonts fell off developers' radars and the whole idea lay dormant until 2009 when both Safari and Firefox (re)introduced @font-face on their browsers and the CSS Working Group introduced a standardized way to load fonts on the web.

While we had the specification for how to load fonts there was no standard font to use, we still had to account for all the different formats supported browsers at the time.

That's where the bulletproof @font-face syntax came in. It tried to support all browsers so we only declare the font once with multiple formats to accommodate different browsers. Over the years there have been multiple versions of the syntax, dating back to 2009:

- Bulletproof @font-face Syntax (2009)

- The New Bulletproof @font-face Syntax (2011)

- Further Hardening of the Bulletproof @font-face Syntax (2011), with “Extra Bulletproofiness” 😀

- How to Bulletproof @font-face Web Fonts (2011)

The next section explores how much it has evolved and whether we still need the full syntax to work with Modern browsers.

The evolution of the bulletproof syntax #

The original bulletproof @font-face syntax, first documented in Paul Irish's Bulletproof @font-face Syntax, looked something like this:

@font-face {

font-family: Open Sans;

src: url("opensans.eot");

src: url("opensans.eot?#iefix") format("embedded-opentype"),

url("opensans.woff") format("woff"),

url("opensans.ttf") format("truetype"),

url("opensans.svg#svgFontName") format("svg");

}The original syntax accounted for the different formats browsers supported at the time and their idiosyncrasies like the double declaration of EOT fonts.

In No @font-face syntax will ever be bulletproof, nor should it be Zach Leat describes the evolution of the bulletproof syntax and what the rationale for the removals are. The final @font-face syntax is:

@font-face {

font-family: Open Sans;

src: url(opensans.woff2) format("woff2"),

url(opensans.woff) format("woff");

}Browsers src attribute will use the first format that they support and, since most browsers that support WOFF2 will also support WOFF we want to place the smallest file first.

This assumes that most of your target users are in modern browsers, we're forcing older browsers to use system fonts:

Make sure that you test your font stacks in your target browsers, particularly if you're targeting emerging markets where users may be working with older versions of operating systems to avoid device upgrades and, potentially expensive, software updates.